Abstract Data Interface and the Black Box Principle

The black box principle represents a fundamental concept in software engineering where components hide their internal implementation details while exposing clean, well-defined interfaces. Users interact with these components through documented interfaces without needing to understand—or even having access to—the internal mechanics. This principle applies at multiple levels: individual functions, classes, modules, and entire systems. In C++, the black box principle manifests through encapsulation, access specifiers, and abstract interfaces that separate what a component does from how it does it. Understanding and applying this principle enables building maintainable, testable, and reusable software where changes to implementation details don't ripple through dependent code.

Encapsulation and Information Hiding

Encapsulation bundles data with the operations that manipulate it while restricting direct access to internal state. Information hiding goes hand-in-hand with encapsulation by deliberately concealing implementation details behind public interfaces. In C++, access specifiers (

private, protected, public) enforce these boundaries at compile time. Private members remain invisible to client code, protecting objects from being placed in invalid states through direct manipulation. Public members form the interface—the contract between the class and its users—documenting what the class provides without revealing how those capabilities are implemented.

// Black box: interface exposed, implementation hidden

class bank_account {

private:

// Hidden implementation details

std::string account_number;

double balance;

std::vector<std::string> transaction_log;

// Private helper methods

void log_transaction(const std::string& description) {

transaction_log.push_back(description);

}

public:

// Public interface - the black box contract

bank_account(const std::string& acct, double initial)

: account_number(acct), balance(initial) {

log_transaction("Account opened");

}

bool deposit(double amount) {

if (amount <= 0) return false;

balance += amount;

log_transaction("Deposit: $" + std::to_string(amount));

return true;

}

bool withdraw(double amount) {

if (amount <= 0 || amount > balance) return false;

balance -= amount;

log_transaction("Withdrawal: $" + std::to_string(amount));

return true;

}

double get_balance() const { return balance; }

};

// Client code sees only the interface

void use_account() {

bank_account acct("12345", 1000.0);

// Clean interface - don't know or care about internals

acct.deposit(500.0);

acct.withdraw(200.0);

// Can't access private members - enforced by compiler

// acct.balance = -100; // ERROR: balance is private

// acct.transaction_log.clear(); // ERROR: private

}

Balancing Public and Private

Determining which components should be public versus private requires careful judgment. Making too much public exposes implementation details that clients might depend on, preventing future changes and creating maintenance burdens. Making too much private creates inefficiencies when legitimate use cases require workarounds or duplicated functionality. The goal is exposing enough to meet client needs while hiding enough to preserve implementation flexibility. Public interfaces should be stable, minimal, and sufficient. Private implementation should be free to change without affecting clients.

// Poor design: too much public exposure

class bad_stack {

public:

std::vector<int> data; // Direct access to internal storage

size_t top_index; // Internal state exposed

void push(int value) { data.push_back(value); }

int pop() { return data.back(); data.pop_back(); }

};

// Clients can break invariants

void misuse_bad_stack() {

bad_stack s;

s.data.clear(); // Breaks stack semantics

s.top_index = 999; // Invalid state

}

// Good design: proper encapsulation

class stack {

private:

std::vector<int> data; // Hidden implementation

public:

void push(int value) { data.push_back(value); }

int pop() {

if (data.empty()) {

throw std::runtime_error("Stack underflow");

}

int value = data.back();

data.pop_back();

return value;

}

int top() const {

if (data.empty()) {

throw std::runtime_error("Stack empty");

}

return data.back();

}

bool empty() const { return data.empty(); }

size_t size() const { return data.size(); }

};

// Clean interface prevents misuse

void use_good_stack() {

stack s;

s.push(10);

s.push(20);

// Can't break invariants - no access to internals

int value = s.pop(); // Guaranteed valid or throws

}

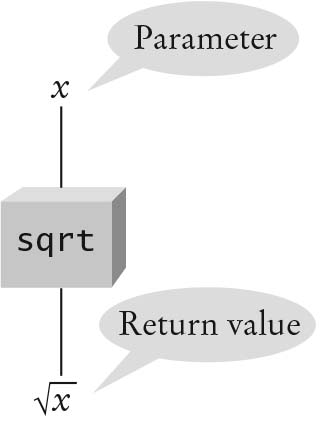

Functions as Black Boxes

Individual functions exemplify the black box principle at its simplest level. A function receives inputs through parameters, performs some computation hidden from the caller, and produces outputs through return values. The caller need not understand the algorithm, only the contract: what inputs are required, what output is produced, and what side effects occur. Consider the standard library's

std::sqrt() function—users know it computes square roots but typically don't know whether it uses Newton's method, a lookup table, or hardware instructions.

Input parameter

x enters the black box labeled sqrt, which produces output √x. The internal computation method remains hidden from the caller.

// Black box function: interface defined, implementation hidden

double compute_hypotenuse(double a, double b) {

// Users see: takes two doubles, returns double

// Users don't see: uses Pythagorean theorem

return std::sqrt(a * a + b * b);

}

// Another black box using the first

double triangle_area(double a, double b, double c) {

// Heron's formula - implementation detail

double s = (a + b + c) / 2.0;

return std::sqrt(s * (s - a) * (s - b) * (s - c));

}

// Usage: just call with inputs, get outputs

void use_functions() {

double hyp = compute_hypotenuse(3.0, 4.0); // 5.0

double area = triangle_area(3.0, 4.0, 5.0); // 6.0

// Don't need to know implementation details

// Can change algorithms without affecting callers

}

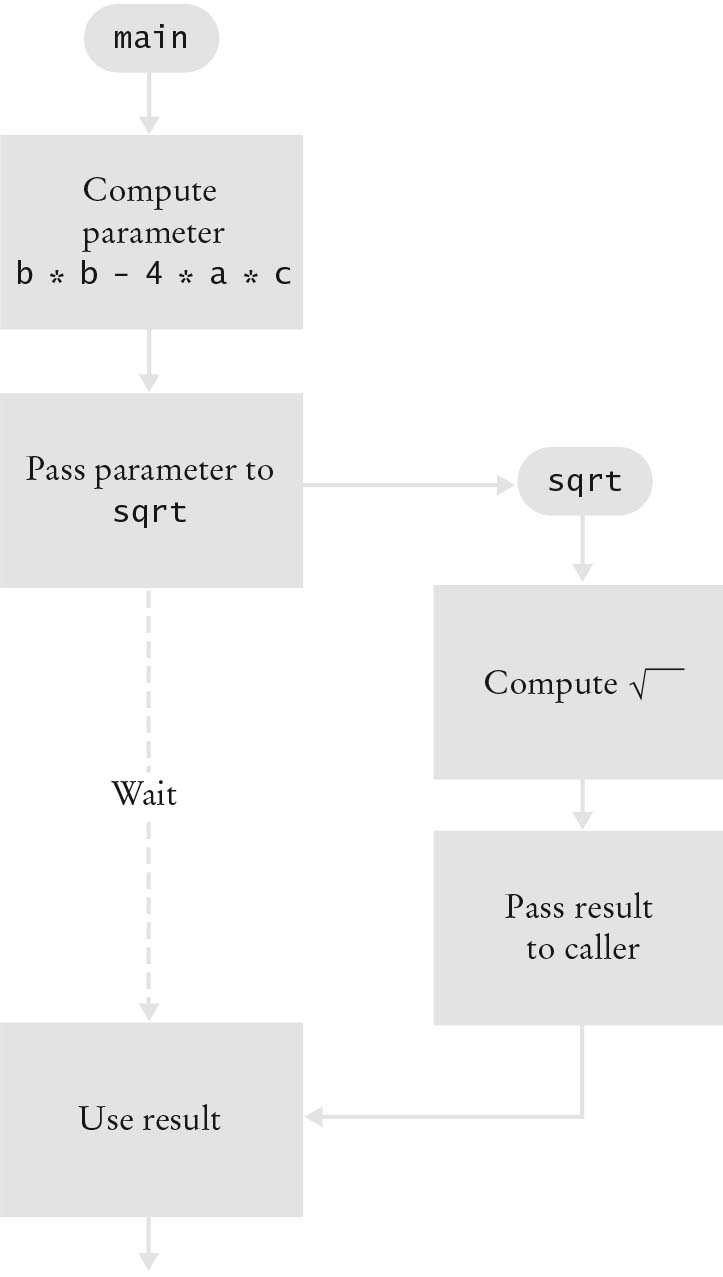

Execution Flow and Function Calls

When a function is called, program execution transfers control from the caller to the called function. Parameter values are passed to the function, which executes its implementation and computes a result. Control then returns to the caller along with the return value. This transfer mechanism is hidden from the programmer—whether parameters are passed by value, reference, or using registers, and whether the call uses stack frames or tail call optimization, remains implementation details. The black box abstraction allows reasoning about program behavior without understanding these low-level mechanics.

The calling function suspends execution, parameters are transferred to the called function, the called function executes and computes a result, and control returns to the caller with the return value. This entire sequence is abstracted behind the function call interface.

double calculate_total(double subtotal, double tax_rate) {

// Called function executes independently

double tax = subtotal * tax_rate;

return subtotal + tax;

}

void process_order() {

double price = 100.0;

double rate = 0.08;

// Execution flow:

// 1. Process_order suspends

// 2. Parameters (100.0, 0.08) passed to calculate_total

// 3. calculate_total executes

// 4. Returns 108.0

// 5. Process_order resumes with result

double total = calculate_total(price, rate);

std::cout << "Total: $" << total << '\n';

}

Black Box Testing vs White Box Testing

Testing strategies divide into black box and white box approaches. Black box testing verifies functionality without examining internal structure, focusing on inputs and outputs as defined by the interface. This approach mirrors how actual users interact with software—they see only the public interface, not the implementation. White box testing examines internal structure, testing individual components, code paths, and implementation details. Both approaches complement each other: black box testing ensures the interface meets requirements, while white box testing verifies the implementation's correctness and handles edge cases that might not be obvious from the interface alone.

class string_processor {

private:

std::string data;

// Private helper - white box testing targets this

bool is_vowel(char c) const {

return c == 'a' || c == 'e' || c == 'i' ||

c == 'o' || c == 'u' ||

c == 'A' || c == 'E' || c == 'I' ||

c == 'O' || c == 'U';

}

public:

explicit string_processor(const std::string& s) : data(s) {}

// Public interface - black box testing targets this

int count_vowels() const {

int count = 0;

for (char c : data) {

if (is_vowel(c)) ++count;

}

return count;

}

std::string remove_vowels() const {

std::string result;

for (char c : data) {

if (!is_vowel(c)) result += c;

}

return result;

}

};

// Black box tests: interface behavior only

void test_black_box() {

string_processor sp("Hello World");

// Test interface contract

assert(sp.count_vowels() == 3); // e, o, o

assert(sp.remove_vowels() == "Hll Wrld");

// Don't test implementation details

// Don't care HOW it counts, just that result is correct

}

// White box tests: implementation verification

void test_white_box() {

// Test internal logic paths

// Test edge cases in implementation

string_processor empty("");

assert(empty.count_vowels() == 0);

string_processor all_vowels("aeiouAEIOU");

assert(all_vowels.count_vowels() == 10);

string_processor no_vowels("xyz");

assert(no_vowels.count_vowels() == 0);

}

Abstract Interfaces and Pure Virtual Functions

Abstract interfaces take the black box principle further by defining pure contracts without any implementation. In C++, abstract base classes containing pure virtual functions specify what derived classes must provide without dictating how. This separation enables polymorphism—code that works with base class pointers or references operates correctly with any derived class implementation. The interface becomes a contract that implementations must fulfill, enabling substitutability and loose coupling between components.

// Abstract interface - pure black box specification

class data_storage {

public:

virtual ~data_storage() = default;

// Pure virtual functions define interface contract

virtual void save(const std::string& key,

const std::string& value) = 0;

virtual std::string load(const std::string& key) = 0;

virtual bool exists(const std::string& key) const = 0;

virtual void remove(const std::string& key) = 0;

};

// Concrete implementation: in-memory storage

class memory_storage : public data_storage {

private:

std::unordered_map<std::string, std::string> data;

public:

void save(const std::string& key,

const std::string& value) override {

data[key] = value;

}

std::string load(const std::string& key) override {

auto it = data.find(key);

return (it != data.end()) ? it->second : "";

}

bool exists(const std::string& key) const override {

return data.find(key) != data.end();

}

void remove(const std::string& key) override {

data.erase(key);

}

};

// Concrete implementation: file-based storage

class file_storage : public data_storage {

private:

std::string directory;

std::string get_filename(const std::string& key) const {

return directory + "/" + key + ".txt";

}

public:

explicit file_storage(const std::string& dir) : directory(dir) {}

void save(const std::string& key,

const std::string& value) override {

std::ofstream file(get_filename(key));

file << value;

}

std::string load(const std::string& key) override {

std::ifstream file(get_filename(key));

std::string value;

std::getline(file, value);

return value;

}

bool exists(const std::string& key) const override {

std::ifstream file(get_filename(key));

return file.good();

}

void remove(const std::string& key) override {

std::remove(get_filename(key).c_str());

}

};

// Code using interface works with any implementation

void use_storage(data_storage& storage) {

storage.save("user", "Alice");

storage.save("email", "alice@example.com");

if (storage.exists("user")) {

std::string user = storage.load("user");

std::cout << "User: " << user << '\n';

}

}

void demonstrate_polymorphism() {

memory_storage mem;

file_storage file("/tmp/data");

// Same code works with different implementations

use_storage(mem); // Uses memory

use_storage(file); // Uses files

}

Modern C++20/23 Concepts as Interface Specifications

C++20 concepts provide compile-time interface specifications that formalize black box contracts. Unlike runtime polymorphism through virtual functions, concepts express requirements statically, enabling the compiler to verify implementations satisfy interface contracts. Concepts document what operations a type must support, making black box boundaries explicit in the type system itself. This approach combines the flexibility of templates with the clarity of well-defined interfaces.

#include <concepts>

// Concept defines black box interface requirements

template<typename T>

concept storage_interface = requires(T storage, std::string key, std::string value) {

{ storage.save(key, value) } -> std::same_as<void>;

{ storage.load(key) } -> std::convertible_to<std::string>;

{ storage.exists(key) } -> std::convertible_to<bool>;

{ storage.remove(key) } -> std::same_as<void>;

};

// Implementation satisfying concept

class vector_storage {

private:

std::vector<std::pair<std::string, std::string>> data;

public:

void save(const std::string& key, const std::string& value) {

for (auto& pair : data) {

if (pair.first == key) {

pair.second = value;

return;

}

}

data.emplace_back(key, value);

}

std::string load(const std::string& key) const {

for (const auto& pair : data) {

if (pair.first == key) return pair.second;

}

return "";

}

bool exists(const std::string& key) const {

for (const auto& pair : data) {

if (pair.first == key) return true;

}

return false;

}

void remove(const std::string& key) {

data.erase(

std::remove_if(data.begin(), data.end(),

[&](const auto& p) { return p.first == key; }),

data.end()

);

}

};

// Function constrained by concept

template<storage_interface Storage>

void process_data(Storage& storage) {

storage.save("config", "value");

if (storage.exists("config")) {

std::string val = storage.load("config");

std::cout << "Config: " << val << '\n';

}

}

// Concept verified at compile time

void demonstrate_concepts() {

vector_storage vs;

process_data(vs); // OK: satisfies storage_interface

// std::string s;

// process_data(s); // ERROR: doesn't satisfy concept

}

Benefits of Black Box Design

Black box design provides multiple benefits that compound as systems grow. Localized changes prevent ripple effects—modifying implementation details doesn't require changing client code as long as the interface remains stable. Testing becomes simpler when components have well-defined contracts verified through their interfaces. Debugging narrows to specific components since interface boundaries isolate problems. Parallel development allows different teams to work independently on components with agreed-upon interfaces. Code reuse improves when components expose clean, documented interfaces rather than implementation details. Maintenance costs decrease when changes are localized rather than spreading throughout dependent code.

Pitfalls of Poor Encapsulation

Violating the black box principle creates maintenance nightmares. Exposing implementation details through public members allows clients to depend on aspects intended as private, preventing future changes. Leaking abstractions where implementation details seep through the interface create fragile code that breaks when internals change. Insufficient interfaces force clients to work around missing functionality, often by accessing internals through questionable means. Over-specified interfaces that promise too much about implementation constrain future optimizations. The key is finding the balance: expose enough to be useful, hide enough to remain flexible.

// Poor encapsulation example

class leaky_cache {

public:

std::unordered_map<std::string, std::string> cache_map; // Exposed!

int max_size; // Exposed!

void put(const std::string& key, const std::string& value);

};

// Clients start depending on exposed internals

void misuse_cache(leaky_cache& cache) {

// Direct access breaks abstraction

cache.cache_map.clear(); // Bypasses eviction policy

cache.max_size = 0; // Creates invalid state

// Now can't change map to different data structure

// Now can't add thread safety

// Now can't change eviction algorithm

}

// Proper encapsulation

class proper_cache {

private:

std::unordered_map<std::string, std::string> data;

size_t max_entries;

void evict_if_needed();

public:

explicit proper_cache(size_t max) : max_entries(max) {}

void put(const std::string& key, const std::string& value);

std::string get(const std::string& key) const;

bool contains(const std::string& key) const;

void clear();

size_t size() const;

};

Conclusion

The black box principle represents fundamental wisdom in software engineering: hide implementation details behind well-defined interfaces, enabling components to evolve independently while maintaining compatibility. From individual functions through classes to entire systems, treating components as black boxes—understanding their contracts without depending on their internals—creates maintainable, testable, flexible software. Modern C++ reinforces this principle through access specifiers enforcing encapsulation at compile time, abstract interfaces enabling polymorphism through pure virtual functions, and concepts specifying interface requirements verified statically. The discipline of identifying what should be public versus private, designing minimal yet sufficient interfaces, and rigorously maintaining abstraction boundaries pays dividends throughout a software system's lifetime. Whether implementing a simple stack class or a complex distributed system, the black box principle guides decisions toward designs that balance expressiveness, flexibility, and maintainability while enabling the parallel development, independent testing, and incremental improvement that characterize successful software projects.