Architectural Partitioning in System Design

Architectural partitioning is the practice of splitting a software system into layers, or tiers, so that each group of components has a clear technical role and a clear set of responsibilities. Some partitions are centralized back-office services; others are widely distributed across departments, mobile devices, or the public internet.

In this module we focus on how responsibilities move between clients, application servers, and database servers. Those choices shape every later design decision—from your C++ class structure to the way objects are deployed and communicate across processes and machines.

Architecture Before Object Design

Architectural partitioning must come before detailed object design. Low-level design needs to support the chosen architecture, not the other way around. When you change the architecture, you change the constraints that classes must satisfy:

- Latency and bandwidth: Remote calls between tiers are slower and more expensive than in-process calls. This affects how you design interfaces and how coarse-grained your objects need to be.

- Memory and resource management: A desktop client, an application server, and a database server have different lifetimes, scaling expectations, and resource limits. Ownership and RAII strategy in C++ often differs per tier.

- Deployment and versioning: A design that works for a two-tier system does not automatically map to a three-tier or n-tier system. Adding tiers usually means introducing new service boundaries, new protocols, and new deployment pipelines.

Because of these factors, we first decide how to partition the system architecturally, and only then refine each partition into C++ classes, interfaces, and components.

Architecture and Technology Choices

Architectural decisions also constrain which technologies make sense. For example, you might decide that:

- A browser or desktop client uses a graphical user interface and talks to services using HTTP, WebSockets, or gRPC.

- Application servers run C++ services that expose a REST or RPC-style API, perhaps behind an API gateway.

- Database servers run a relational DBMS and provide the persistence tier for business entities.

Historically, technologies such as CORBA were used to connect distributed objects across tiers. In modern systems, CORBA is mostly of historical interest; new code typically prefers gRPC, HTTP/JSON APIs, or message-queue –based integration. When maintaining legacy systems, technologies like CORBA are usually isolated at integration boundaries and wrapped with simpler service interfaces.

Throughout this module, we will treat architectural patterns such as two-tier, three-tier, and n-tier as deployment targets for your object model and C++ components.

Learning Objectives

After completing this module, you will be able to:

- Explain the purpose and function of architectural partitioning.

- Create architectural partitions and define their responsibilities.

- Describe how responsibilities are distributed in two-tier, three-tier, and n-tier architectures.

- Apply deployment diagrams to model how C++ components are mapped to physical machines and processes.

Client–Server Tiers

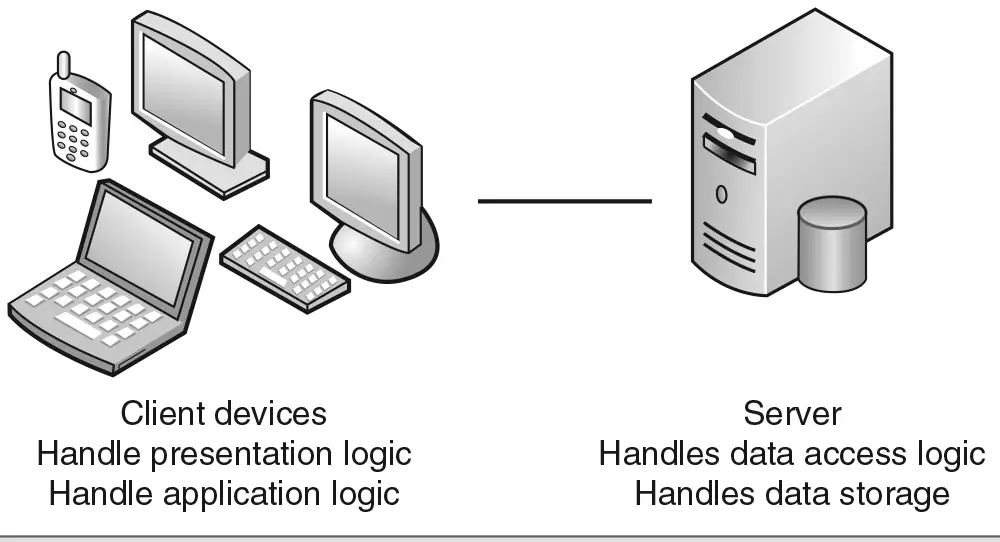

There are many ways to partition application logic between clients and servers. The simplest configuration is shown in Figure 5-1. In this two-tier architecture, the client is responsible for the user interface and most application logic, while the server focuses on data access and storage.

Two-tier client–server architecture. Client devices talk directly to a single server. The client tier hosts both presentation and application logic; the server tier hosts data access logic and persistent storage.

-

Client devices

- Handle presentation logic (UI, input, output).

- Handle application logic (validations, workflows).

-

Server

- Handles data access logic (queries, transactions).

- Handles data storage (database or file system).

Figure 5-1: Two-Tiered Client–Server Architecture

This configuration is sometimes called a fat client (or thick/rich client) architecture because most of the behavior executes on the client machine.

| Component | Where it runs | Style label |

|--------------------|-----------------------|--------------------------|

| Presentation logic | On the client devices | Fat / Thick / Rich Client|

| Application logic | On the client devices | |

| Data access logic | On the server | |

| Persistent storage | On the server | |

Why Two-Tier Fat Clients Were Popular

Historically, two-tier client–server systems were common for line-of-business applications:

- Traditional Win32 desktop applications connecting directly to Microsoft SQL Server or Oracle.

- Delphi, PowerBuilder, or Visual Basic applications using ODBC, JDBC, or ADO connections to a database.

- Many internal corporate client–server applications prior to widespread web deployment.

Strengths of a Two-Tier Fat-Client Architecture

- Rich and responsive UI: The UI can use the full capabilities of the client machine without round-tripping to a server for every interaction.

- Fast local processing: Business rules run locally, so complex validations and calculations can be very responsive.

- Efficient network usage: Only data and commands are sent over the network; no HTML pages or rendering instructions are transmitted.

Limitations for Modern Systems

- Challenging deployment: Every client machine needs the application installed and updated. Rolling out a new version can become a significant operational task.

- Tight coupling to the database: Clients often embed connection strings and credentials, making security and schema changes harder to manage.

- Security concerns: With business rules on the client, logic can sometimes be reverse-engineered, modified, or bypassed.

- Limited scalability: Scaling to hundreds or thousands of users stresses both the database and the support burden on client machines.

- Device and OS diversity: Fat-client solutions rarely run consistently across desktop, web, and mobile platforms.

Where Two-Tier Still Fits

Two-tier architectures remain useful when you need powerful desktop clients with rich local tooling and a relatively small, controlled user base—for example:

- Desktop productivity tools and IDEs.

- Trading or analytics terminals in finance.

- Specialized engineering applications that sync data to a central server.

Three-Tier and N-Tier Architectures

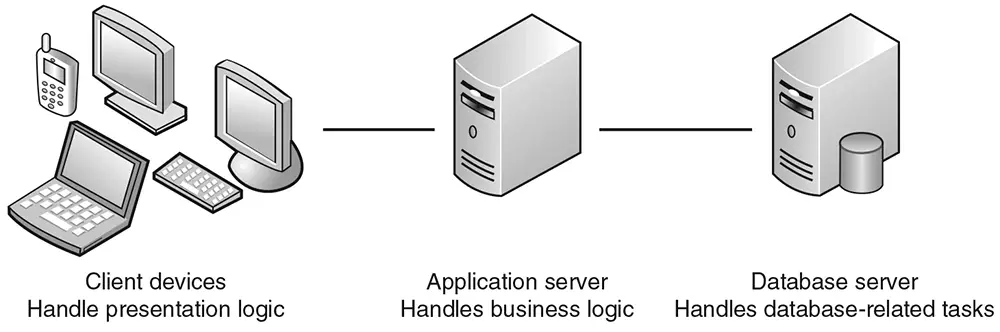

A three-tier architecture adds an intermediate application server tier between clients and the database. The client tier focuses on presentation, the middle tier encapsulates business rules and system services, and the data tier manages persistence.

Typical responsibilities in a three-tier system are:

- Client tier: Browser, desktop, or mobile UI. Handles input, output, and a small amount of client-side validation.

- Application tier: C++ (or mixed-language) services that implement business rules, orchestration, security checks, and integration with other systems.

- Data tier: Relational or NoSQL databases that manage data access logic, indexing, transactions, and long-term storage.

The application tier can itself be split into additional layers—API gateways, microservices, background workers, and reporting services. When you add these extra layers, the result is often described as an n-tier architecture.

Example: Web-Based E-Commerce System

Modern web-based e-commerce systems are classic examples of three-tier or n-tier architectures:

- The client tier is a web browser or mobile app that sends HTTP or gRPC requests and renders product pages.

- The application tier contains services that manage shopping carts, pricing rules, taxes, shipping calculations, and payment authorization.

- The data tier stores product catalogs, orders, customers, and inventory in one or more databases.

Because business logic is centralized in the application tier, multiple front ends (web, mobile, desktop tools, batch jobs) can share the same rules and services. This reduces duplication and makes it easier to evolve the system.

How This Module Uses Architectural Partitioning

The rest of this module builds on these architectural patterns. We will show how to:

- Map use cases and domain concepts onto tiers.

- Design C++ classes that are aware of latency and deployment boundaries.

- Use deployment diagrams to communicate how components are partitioned across clients, application servers, and databases.

By the end of the module, you should be comfortable choosing an architecture (two-tier, three-tier, or n-tier), understanding the trade-offs, and designing object models that align with that architecture.